Last Modified: 2:13pm 30/04/2021

Metabolic Derangements in Diabetes; HHS and DKA

For specific advice on DKA management click below:

https://www.mkuh.nhs.uk/diappbetes/app/diabetic-emergencies/diabetes-ketoacidosis-dka

For specific advice on HHS management click below:

https://www.mkuh.nhs.uk/diappbetes/app/diabetic-emergencies/hypersomolar-hyperglycaemic-state-hss

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome (HHS) are two acute complications of diabetes that can result in increased morbidity and mortality if not efficiently and effectively treated.

Mortality rates are 2–5% for DKA and 15% for HHS, and mortality is usually a consequence of the underlying precipitating cause(s) rather than a result of the metabolic changes of hyperglycaemia. Effective standardized treatment protocols, as well as prompt identification and treatment of the precipitating cause are important factors affecting outcome.

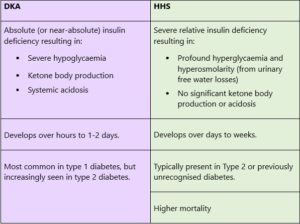

Although both HHS and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) are often discussed as distinct entities, they represent two points on the spectrum of metabolic derangements in diabetes.

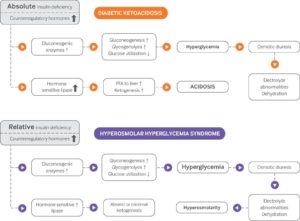

The exact pathophysiologic mechanisms of DKA and HHS are complex, but in general, the pathogenesis begins with insufficient insulin and high levels of counterregulatory hormones (glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, and catecholamines).

This results in hyperglycaemia, which promotes an osmotic diuresis, leading to dehydration and electrolyte loss. In both conditions, insulin levels are insufficient for peripheral tissue glucose utilization, resulting in hyperglycaemia.

Approximately 33% of patients with hyperglycaemic crises present with a mixed picture of DKA and HHS.

HHS is the type 2 diabetes equivalent of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in type 1 diabetes individuals. Its metabolic differences occur because in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus there is a small quantity of insulin remaining enough to suppress lipolysis and the associated acidosis.

HHS occurs less frequently when compared to diabetic ketoacidosis but once it occurs it has a higher mortality rate of about 15%.

BMJ Best Practice 2021

DKA vs HHS

Diabetic Council

Pathogenesis of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome. FFA=free fatty acids

Prevention of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS

Recurrent episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS can be prevented in many cases. The cause of every episode of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS should be determined so that tailored education and intervention can be provided to the patient to prevent recurrence (see below).To prevent readmission to hospital and visits to the emergency department, education based on the needs of the individual patient should be provided before discharge. This education, sometimes called “survival skills” education, can include a review of the causes, signs, and symptoms of impending diabetic ketoacidosis, as well as what to do and who and when to call when symptoms develop. Providing patients and their family members with information on how to manage their diabetes drugs during periods of acute illness can reduce the metabolic decompensation that can occur with inappropriate reductions or omissions of insulin doses.

Identification and treatment of underlying causes and prevention of recurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome

- Assess and manage reasons for insulin non-adherence (if applicable)

- Facilitate treatment or social services for patients with untreated or poorly controlled psychiatric disorders

- Refer patients with substance or alcohol use disorders to treatment programs

- Provide education on appropriate sick day management (if applicable) and refer the patient to a formal diabetes education program after hospital discharge

- Treat treatable precipitating causes such as infection, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, or trauma

Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic syndrome: review of acute decompensated diabetes in adult patients

BMJ 2019; 365 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1114 (Published 29 May 2019)